press

|

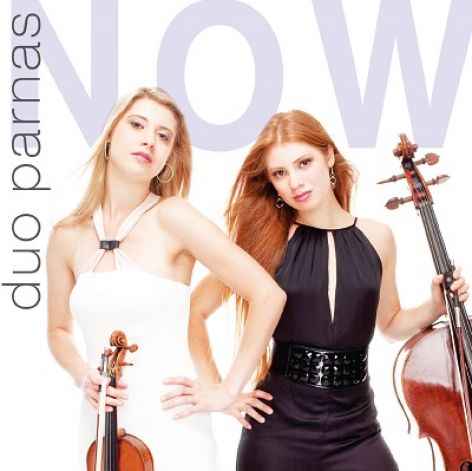

'NOW' IS NEWEST FROM DUO PARNAS

"Now" is the title and also the time frame for the latest new CD from Duo Parnas, violinist Madalyn Parnas and cellist Cicely Parnas, the natives of Stephentown who've been on the rise as classical musicians since their teens. It's a clever name for a disc made up of all contemporary works. Yet "Now" has always been a rather fleeting matter, especially when it comes to the Parnas sisters. When I profiled the girls in 2009, they were always on the go, shuttling between studies at the New England Conservatory, The College of Saint Rose and Siena and Bard colleges. And now they're still something of a blur as they dash from one appearance to another in different parts of the country and even on different continents. In October, they'll be spending a couple weeks in China at two different international festivals. In November, they perform the Brahms Double Concerto in Alexandria, Va., and in January they'll play three different concertos with the Schenectady Symphony at Proctors. Meanwhile, there's their solo work. In April, Madalyn performs with the London Philharmonic and Cicely makes her Boston recital debut. And that's just some of the highlights. Now, on to the CD. It was recorded last winter and spring at Indiana University, where the young women earned their artistic diplomas, and includes eight different violin/cello duos. Many of the composers worked with the Duo Parnas, either in creating the pieces or for some coaching on the interpretation. Taken as a whole, the disc is full of elegance and personality, thanks to the always fine playing. And yet the language of the music changes quite a bit from piece to piece. That's evidence that, in this eclectic, anything-goes era of American music, it's not easy to pinpoint what "now" means. The opener is a mostly cheerful five-movement suite by William Bolcom, itself an exercise in eclecticism. Next is the soulful and impassioned "De Profundis," written for Duo Parnas by Stephen Dankner, who lives in Williamstown, Mass. Another piece written for the sisters is Paul Moravec's "Parnas Duo," a stirring essay, rather conservative in its unabashed use of tonality. Contrast that to the briefest and spikiest piece, Charles Wuorinen's dissonant "Album Leaf." My favorite of the selections is the five-movement Partita from Seymour Barab, a New Yorker who died in July at age 93 and was best known for his lighthearted chamber operas. In the CD booklet, Cicely Parnas describes the piece as "boisterous and groovy!" I can't think of a better way to put it. "Now" is available from Shefield Lab Recordings (http:www.shefieldlab.com). Keep up on the Parnas Duo at http://www.parnasmusic.com. |

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES

ALLAN KOZINN 6/13/2007 |

BAD IS GOOD IN ONE-ACT OPERAS FEATURING THE SIN OF INFIDELITY

Nothing gets an opera moving like one of the seven deadly sins, and if you can make the sin comic rather than deadly, so much the better. Seymour Barab has written several one-act comic operas and short operatic scenes about lust — more specifically, adultery — and on Monday evening the After Dinner Opera Company offered several at the Leonard Nimoy Thalia Theater at Symphony Space. At 86, Mr. Barab is a prolific composer who also had a career as a cellist and gamba player. He writes his own librettos, which are clever, funny and often rhymed, and he sets them to music with an easygoing theatricality. No grand stylistic points are made here, except perhaps that directness and lyricism are both sensible and useful if your goal is simply to entertain. The company opened its program with “Savoir Faire,” a vignette from Mr. Barab’s “American Punchlines.” Here three drinking buddies each define savoir-faire in terms of a husband’s reaction to finding his wife in bed with another man. One suggests a husband who apologizes for arriving without calling first; another suggests the husband’s offering his wife’s lover a drink. In the third tale it’s the lover who demonstrates savoir-faire: he asks the pistol-wielding husband not to shoot him until the lady has been sufficiently satisfied. Gracefully harmonized trios begin and end the piece. In “Everyone Has to Be Free” the philanderer is a nightingale who enjoys warbling to a young princess (in a fairy tale within the opera) but needs to get back to his wife. The frame for that story is a conversation between a recently widowed man and his wife’s ghost. Their marriage had been blissful, but he had a suitcase packed in case he needed a night away, so to speak. He never took the option, but when he opens the suitcase to see if his suit still fits, he discovers one of his wife’s negligees. The final panel, “The Husband, the Wife, the Lover,” is a set of five scenes exploring infidelity and discovery, and a raft of subsidiary themes, in the same spirit of lyrical geniality and taboo smashing: in “My, My!” Mr. Barab gets laugh lines into the final moments of a double murder and suicide. The singers were mostly students or recent graduates of Mercyhurst College in Erie, Pa., where the After Dinner Opera Company is based. The best performances were by Jaqueline Edford, Dennis TeCulver, Kate Amatuzzo and Mark Donlin, but the others made strong contributions as well. They were Matthew Makay, Lydia Howery, Nicole Marie Gasse, Rachel Myers and Scott Spinnato. Louisa Jonason directed the production. |

|

OPERA FOR YOUTH JOURNAL

Vol. 17(4) 1994-18(1)1995 Martha L. Malone |

THE TOY SHOP: An Opera in One Act for a Young Audience

For Professional Singers to Perform for Elementary School Children (K-6) Seymour Barab is one of the foremost composers of children's opera in the United States. He has written 27 operas for young audiences or performers to date, and his works enjoy wide popularity. The New York City Opera Education Department commissioned TheToy Shop and presented the first production at Lincoln Center in 1978. In the same year the New York City Opera production traveled to Washington, D.C., where it was performed at the second annual convention of Opera For Youth, Inc. at the Kennedy Center. Since its publication by G. Schirmer in 1980, this work has become a favorite of opera companies and audiences throughout the country. In 1984 the Central Opera Service Directory of OperasI Musicals for Young Audiences called the Toy Shop, "among the ten most performed contemporary operas within the past five years." The opera has a duration of fifty minutes and is organized in twelve scenes. The libretto, written by the composer, tells the story of a toymaker whose love for his creations brings them to life. The Toy Shop is an entertainment of the highest quality in both libretto and music. Like all great works of art and literature, it explores larger questions - in this case, matters of human behavior and relationships - while constantly engaging the attention of its intended audience. The young audiences who attend performances of this opera will have a boisterous hour of fun and will also come away with a sharper awareness of the value of their family relationships. Because of its small scale and the accessibility of the music and text, The Toy Shop is a good choice for professional companies and college-level opera programs who want to reach the children and families in their communities. Given the beauty of the music and the excellence of the libretto, which is both clever and moving, it is no surprise that this opera has become exceedingly popular with opera organizations all over the United States. Seymour Barab's understanding of young audiences is evident in the libretto of The Toy Shop: The composer/librettist's choice of locale and subject matter, his perceptive handling of parent/child and sibling relationships, and his sensitive incorporation of concerns common to most children are important factors in the success of this opera. The toy shop setting and the characters - a toy-maker, a magician, and three life-sized toys - have obvious appeal for children. The elements of magic and mystery around which the story is built have been principal themes in childrens' stories for centuries.Pinocchio, the nineteenth-century story by Carlo Collodi, Margery Williams' story book The Velveteen Rabbit, and Walt Disney Studios' 1991 animated cartoon film version of Beauty and the Beast (after the French fairy tale) are examples of the many children's tales in which inanimate objects - often toys - come to life. Many more factors make this an effective entertainment for children. For example, the toy-maker and Aaron Blunder are good and bad characters, respectively, who are as clearly defined in their roles as cartoon characters Superman and Batman and their antagonists. In addition, both suspense and slapstick comedy pervade scene 6, as the dolls play hide-and-seek with Blunder, Paul kicking him at every opportunity. The final surprise of the opera - the arrival of the gorilla Paulette and her pursuit of the villain - is a revelation sure to cause uproarious delight in young audiences everywhere. Paul and Pauline, the life-sized dolls, are the "children" of the toy-maker, and interact as siblings. In the opening scene the libretto introduces a subject of intense interest to most children with the toy-maker's announcement that tomorrow is the dolls' birthday, and that they will have a party and a wonderful present. Paul and Pauline's expressions of concern about deeper issues which are important to children convey Barab's skill in writing for children more subtly; for example, Pauline wants to explore the world and have adventures, chafing at the restrictive ways of the overprotective toy-maker, while Paul wants to stay at home within the security of his beloved father's care. All children experience conflicting emotions like these as they begin to assert their independence from their parents. Young children also feel empathy with Pauline's wish that she were able to cry when she is upset, so that she could begin to feel better, and with Paul's desire to tell "Dad" that he loves him. Barab weaves these concerns into the plot as natural outgrowths of the situation. Although this libretto contains no overt political statements, Barab handles the gender roles and familial relationships of his characters with perception and sensitivity. His toy-maker is an adult male character who differs greatly from the majority of those found in the realm of popular entertainment. He is a man who is not embarrassed by the physical and verbal expression of affection and who eschews the pursuit of money or power in favor of following a vocation which provides him with creative and emotional fulfillment. Likewise, Paul and Pauline defy the usual sexual stereotypes, for here the female child longs for adventure, while her brother is afraid of the dangerous world outside and wants to remain under his father's protection. In addition, it is Paul rather than Pauline who demonstrates concern about the relationships between family members, saying in scene 5, 'We need each other, and Dad needs us both.' To Barab's credit, however, the libretto never becomes dogmatic; rather, the characters interact naturally, without the encroachment of any didactic overtones. The sibling relationship between the dolls undergoes rapid transformations from antagonism to camaraderie in a delightfully lifelike manner, and the toy-maker alternately scolds and praises the children as any parent would. Repetition of material is an important element in stories and dramatic presentations written for children. Verbatim repetition of text in parallel dramatic situations brings predictability to - and thus, comfort with - an unfamiliar story as well as enhancing the pleasure with which the audience anticipates the outcome of similar situations in the plot. In scene 2, for example, Paul asks Pauline what reason she has to be sad. Her response is, 'You want the whole list or just a few examples?' When a parallel situation occurs in scene 5 (Pauline asks Paul what his reasons are for not going with Aaron Blunder), her brother quotes her response from scene 2. The most extensive use of repetition in the libretto of the Toy Shop is the toymaker's refrain, which is taken from his initial aria. He sings, "I am a happy man, I am" numerous times during scene 1, opening the scene with this four-measure theme and singing it again as he exits. His ebullient spirit finds expression in this song again as he enters joyfully at the end of scene 9 to announce to the toys that he has finished constructing Paulette. The toy-maker also closes scenes 4 and 10 with brief versions of this refrain: in both cases he sings the text as he exits, although he is actually quite worried and sad in scene 4, and scene 10 finds him alternating between despair and elation. In this way Barab uses repetition of his refrain to define the toy-maker's character as a jolly man who is determined to maintain a positive frame of mind even when he is agitated. The winding of the dolls (three turns of the key) to the accompaniment of three statements of the toy-maker's "I love you" is significant to the development of the story. The first instance occurs in scene 2, when Paul gives Pauline three turns with the key and then describes how good the winding feels when the toy-maker does it. In scene 3 the toy-maker winds both dolls up in turn, telling them that he loves them with each turn of the key. The repeated action and words form a ritual which becomes the agent of change in the final scene, when the key is lost, the toy-maker repeats his "I love you" three times to each doll without the accompanying winding, and the dolls miraculously come to life. The larger theme of the libretto is that it is love which makes things real. In this respect Barab follows the tradition of such works of children's literature as the previously mentioned Pinocchio and 7he Velveteen Rabbit, in which the love of a toy for a human being (or vice versa) brings a toy to life. In fact, several parallels can be drawn between the libretto of 7he Toy Shop and the story of Pinocchio.Barab's toy- maker is clearly a descendant of Geppetto, the childless marionette-maker, just as Paul and Pauline, the life-sized mechanical dolls, are closely related to Pinocchio, the marionette-boy. Furthermore, it is after their brush with the wickedness of the outside world that Paul and Pauline come to a full realization of the extent of the toy-maker's love for them; their experience with the evil magician has a direct parallel with Pinocchio's misfortunes at the hands of dishonest showmen and wicked schoolboys. In Pinocchio the marionette becomes human only when he has learned to love unselfishly, and the story centers around his lesson alone. Barab's Paul and Pauline, however, are transformed into human beings after the magician repents his wickedness and after the toy-maker vows that he loves the dolls even though they are unable to dance. Unlike the people who surround Pinocchio, all of the characters in The Toy Shop experience significant growth in understanding themselves and others: Aaron Blunder undergoes an epiphany through which he changes from a greedy, wicked magician into a person who knows that love is stronger than any other power; Paul learns that his father's love provides more nourishment than does his physical care; Pauline sees that she must not trust flattery, finds out that people are not always what they seem to be, and learns the value of love which is faithu rather than glamorous; and the toy-maker comes to understand that his obsessive over-protectiveness was a selfish and destructive manifestation of his love for his children. The libretto of The Toy Shop contains humor, mystery, suspense, danger, and magic which engage its audiences while it gently teaches fundamental moral lessons. |

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES

BERNARD HOLLAND 1/27/85 |

MUSIC: DUETS BY LIBOVE AND LUGOVOY

Charles Libove and Nina Lugovoy play regularly at the Merkin Concert Hall as a violin-piano duo, and Wednesday night they returned for a program of the new and the unusual. Seymour Barab's new ''Duo'' referred constantly to old ways of hearing harmony, but its playful shifts in phrase length, its militant repetitive quality in the first movement and the more conciliatory Andante that followed made music that always grasped our interest. There were also Ildebrando Pizzetti's ''Tre Canti,'' a darkly colored and pleasantly anachronistic piece from the 1920's, Mozart's more familiar E-flat Sonata (K. 380), and the Richard Strauss Sonata in the same key from his early years. Mr. Libove and Miss Lugovoy are such ardent and musical players that the occasional bumps and blurs of execution barely disturbed the music. One could have expected bigger problems in the Strauss, with all its virtuoso effusions, but both players cut through technical grandness to create something very touching indeed. |

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES

BERNARD HOLLAND 5/16/85 |

MUSIC: 'FARCE,' BY BARAB

SEYMOUR BARAB'S ''Tour de Farce,'' a pair of one-acters at the After Dinner Opera last Sunday night, is not opera in the ominous sense of that word. Mr. Barab writes his own words - they are mostly in verse and often funny -and shapes a continuous flow of pleasant music for them to ride on. The style lies somewhere between Gilbert and Sullivan and Cole Porter, with little ethnic gestures thrown in as needed; and though this music makes no pretense of depth or intensity, one is impressed at how naturally it appears - seemingly without doubt or hesitation. Both pieces use two characters: ''Out the Window'' comments on urban marriage, philandering and the legal profession; ''Predators'' portrays a particularly vicious war of nerves between Count Dracula and a Jewish mother on Riverside Drive. Nothing is more difficult than to be consistently funny, but Mr. Barab does fairly well in ''Out the Window.'' Its companion has moments (Dracula as a victim of Communist bureaucracy is a nice conceit, for example, and there is also a Charles Addams-ish ballad about childhood in Transylvania). Faced with two of show business's stock characters, however, the humor sometimes dips into the obvious. These really are operas, of course, offering a smooth amalgam of set pieces, through composed dramatic interchange and spoken dialogue. The singers - Jocelyn Wilkes and Bill Bonecutter - are very good. The simple staging and scenery by Richard and Beth Flusser do their job. And Conrad Strasser plays Mr. Barab's music on the piano with endearing enthusiasm. ''Tour de Farce'' has four future performances at the Third Street Music School on East 11th Street. They are Saturday and Monday evenings with two more on Sunday. |

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES

RAYMOND ERICSON 6/11/78 |

THE TOY SHOP

"Seymour Barab's "The Toy Shop" now being shown at the Lincoln Center Library Auditorium...makes an effort to explain what opera is as well as to serve as an example of the art form. Seen last Thursday, with children from the ages of 8 to 11 in attendance, the opera seemed to work very well. As narrator, Jon di Savino won the audience's attention like the master of ceremonies on a television quiz show. He then explained the mysteries of recitatives, arias, ensembles and voice ranges, with the help of the cast. "The Toy Shop" proper is a simple confection about a toymaker, two of his doll creations, Paul and Pauline, and Aaron Blunder, the magician who wants to steal them. The dolls start out mechanically activated and wishing they were real ("If only I could cry, how happy I would be.") They discover that "love is the key" that brings them to life. It is a simple charming fable, adroitly written and composed by Mr. Barab, which rarely found the audience restless. One toddler said that she liked the opera very much, but was most taken with the "baboon," a large monkey that entered the story midway in the plot..." |